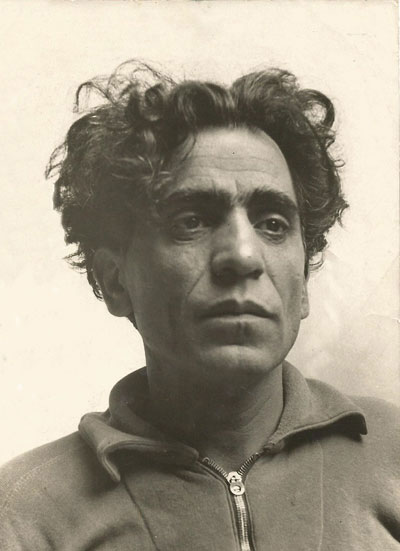

x Jussuf Abbo was born on 14 February 1890 in Safed (Palestine, Ottoman Empire) and died on 29 August 1953 in London.

He was a sculptor and printmaker who had a successful career for over twenty years in Germany before fleeing in 1935

to the United Kingdom.

Abbo was born into a large Jewish farming community suffering at the time under the dominant rule

of the Ottoman Empire. He was the last-born of eight - all the other children were girls. His schooling began at the village

cheder (Jewish religious instruction) but later in a primary school where he began to show talent (particularly in drawing).

Recognised as intelligent and gifted, he obtained a place in a French Alliance Israelite School in Jerusalem. Once his studies

finished there, he was destined, as an outstanding student, to receive a free passage to South America (probably a cultural

colonisation project). He didn't go - he quarrelled with the headmaster and accepted work as a building labourer

instead. He had the reputation of being a lively, opinionated and even arrogant young man. As a labourer on a restoration

site being led by an architect, Hoffmann, on behalf of the German government, Abbo was noticed and was rapidly promoted to

the drawing-office and to stone-carving. He was offered an assured place at a Berlin School of Art if he wanted it. Meanwhile

he worked for some months for an English painter and archaeologist in Tiberias. He was able to save enough money and finally

shook the dust of the Middle East from his feet and arrived in Berlin as a citizen of the Ottoman Empire.

Abbo was born into a large Jewish farming community suffering at the time under the dominant rule

of the Ottoman Empire. He was the last-born of eight - all the other children were girls. His schooling began at the village

cheder (Jewish religious instruction) but later in a primary school where he began to show talent (particularly in drawing).

Recognised as intelligent and gifted, he obtained a place in a French Alliance Israelite School in Jerusalem. Once his studies

finished there, he was destined, as an outstanding student, to receive a free passage to South America (probably a cultural

colonisation project). He didn't go - he quarrelled with the headmaster and accepted work as a building labourer

instead. He had the reputation of being a lively, opinionated and even arrogant young man. As a labourer on a restoration

site being led by an architect, Hoffmann, on behalf of the German government, Abbo was noticed and was rapidly promoted to

the drawing-office and to stone-carving. He was offered an assured place at a Berlin School of Art if he wanted it. Meanwhile

he worked for some months for an English painter and archaeologist in Tiberias. He was able to save enough money and finally

shook the dust of the Middle East from his feet and arrived in Berlin as a citizen of the Ottoman Empire.

Jussuf Abbo arrived in Germany in 1911 and began studying at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin in 1913. By 1919 he had

a master studio in the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts. Throughout the 1920's he exhibited in top galleries throughout Germany and

was a well known portrait sculptor and printmaker and an active member of the Berlin avant-garde artistic community. Much of his

work, being partially abstract with an emphasis on psychological state and emotion, could be considered "Expressionist".

As a person, Abbo was flamboyant and charismatic. Many of his wealthy and powerful patrons, clients and friends were

Jewish. He was known for his bohemian and eccentric lifestyle, an exotic artist from the Orient, apparently living for sometime

in a Bedouin tent in his large Berlin studio. He was part of the group of friends of the Expressionist poet and playwright,

Else Lasker-Schüler, whom he portrayed on several occasions and who

in turn wrote a poem about him.

As a person, Abbo was flamboyant and charismatic. Many of his wealthy and powerful patrons, clients and friends were

Jewish. He was known for his bohemian and eccentric lifestyle, an exotic artist from the Orient, apparently living for sometime

in a Bedouin tent in his large Berlin studio. He was part of the group of friends of the Expressionist poet and playwright,

Else Lasker-Schüler, whom he portrayed on several occasions and who

in turn wrote a poem about him.

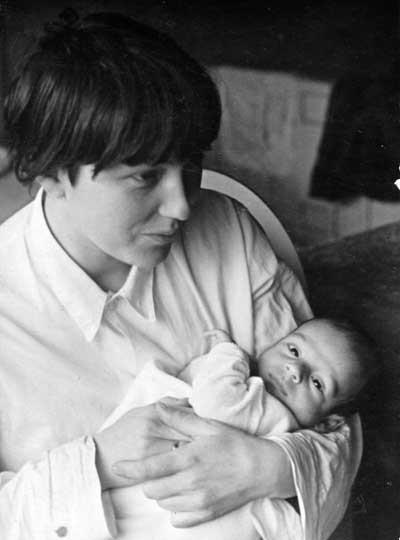

By 1933 he had met Ruth Schulz, a fine art student and they intended to marry. In 1935, with the National Socialists in power,

he suffered persecution because of his Jewish origins and artistic inclinations, and as a result was unable to continue working.

He fled from Nazi Germany to the United Kingdom with his wife and their first child. By 1937, his work, branded as "Degenerate Art"

in Germany, had been removed from all public museums by the Nazi regime. Most of the works removed were destroyed.

Losing one's Artistic Existence - Jussuf Abbo in Exile

By Ruth Abbo (maiden name Schulz)Living under threat in Nazi Germany

I got to know my husband in 1933. We wanted to marry as soon as possible...

I got to know my husband in 1933. We wanted to marry as soon as possible...

...When I, and then also my father, kept on receiving threatening anonymous letters because of my relationship with a non-Arian, I moved in with my uncle for a while...

...It meanwhile turned out that my husband had become stateless during his long stay in Germany. He had originally come to Germany holding a Turkish passport, because the Levant had been under Turkish rule at the time. Unfortunately, as an artist, he had not bothered about such formalities: he believed that both his long stay in Germany and his work would suffice to guarantee him the same rights as a German citizen. By this time it was 1934, and the persecution of the Jews was in full swing. Our closest friends treated us as a married couple, but we were not allowed to marry at the registrar's office...We were forced to live separately time and again and constantly in danger of being reported to the authorities. During the last few months in which I studied at the college of applied arts, I incurred the hostility of members of certain Nazi circles for refusing to join a National Socialist organisation and they continually kept an eye on me...

...My husband was incredibly depressed and in a constant state of extreme tension. It was impossible to work as an artist under these circumstances. Apart from all the other dangers, we had got to the point where it was no longer possible for us to earn a living in Germany. We had to abandon our huge studio in Herbert Strasse. It was quite a task, involving great expense and considerable losses, especially as we had to move in a big hurry. We decided to take only my husband's works - as far as it was at all possible - and to salvage his tools, his heavy turntable, and so on. Unfortunately, I cannot say what happened to the rest of our things because I left Berlin in August 1934, in compliance with my husband's wishes, and waited in Fischerhude near Bremen for our departure. We were expecting our first child to arrive in November. My husband was worried about my health. Not only that, it was also dangerous for us to stay together in Berlin. Under no circumstances could we allow the child to be born in Germany. Our first hope was to find refuge in England.

Some time before, two galleries in London had expressed a desire to hold an exhibition of all our works. We also hoped that we would be able to marry at a registrar's office at long last. My husband had been working himself to death during the weeks previous to our departure. Even so, a lot of things that were standing around in foundries, in galleries and on commission at art dealers' had to be left behind. At the same time, he had been trying to get a passport so that he could enter another country. He wasn't very successful and ultimately hoped that he would at least be able to leave Germany with some provisional documents. At the end of October 1934, we arrived at the Dutch border. They refused to let him enter the country. The Dutch vice-consul in Bentheim promised to do everything at his disposal to help us, and he kept his word. We stayed in Bentheim for about two weeks, hoping that things would turn out for the best. My husband was in a terrible state of nervous exhaustion...Our hotel was swarming with members of the SS. We noticed that we were being watched. Things were starting to turn ugly. I had to leave on my own as quickly as possible.

...My husband was on the verge of a nervous breakdown, but still hoped that he would be able to follow me in two or three days' time...(The Hague)

Our final preparations before we fled

At about 6 p.m. I finally learned from my husband that he was not allowed to enter the country and had to return to Berlin as soon as possible and try once more to obtain the necessary documents. He was very worked up, and as there was no point in trying to calm him down any more, I remained silent about my own condition...

My husband had meanwhile returned to Berlin. Our letters were censored and it was impossible to go into great detail when we wrote to one another...(Worpswede)

...My husband returned to Berlin and only managed to get to Worpswede for a few days now and then...My husband had got in contact with the Egyptian ambassador in Berlin. If I remember correctly, his name was Monsieur Kemal Pascha. He was very interested in my husband's work and full of compassion for my husband's tragic plight. He managed to get us an Egyptian passport, as my husband's father was a native of Egypt. However, it took until summer 1935 before all the formalities were settled and the passport was finally authorised...My husband was not able to work. He hadn't had a studio or a regular place to live in since 1934. In summer 1934, my husband's tools and turntables, were transported to Hamburg, where they awaited shipment.

In March 1935, at the kind invitation of Mr. and Mrs. Karl August von Joest, my husband spent a few weeks at Eichholz Palace near Bonn, where he made drawings of their children. His stay there was an extremely welcome break from all the harassment he had been through, as he really was close, physically and mentally, to having a breakdown...(Worpswede)

Late one night, Mr. Bamberger (then proprietor of the Bamberg Department store in Bremen) sent us a car. We spent a few hours in his house in Bremen and set off for good early in the morning. We left Germany on 20 September 1935. There was a little money available for us in Holland. My husband had sold two of his works to a collector. We hoped that we would manage to survive for the first few weeks in England if we watched our money very carefully. We landed in England on 26 September 1935. We first rented a furnished garret at 1 Grove Terrace, Parliament Hill in North London. Although it was an indescribably gloomy, wretched and unhealthy place to live, we still had to pay a relatively high rent. At least we could hope for a turn for the better in the near future: the Wilderstein Gallery and the Leicester Gallery were prepared to stage an exhibition in the coming winter season.

Attempts to make a new start as an artist

My husband had some very excellent recommendations for a number of collectors and families of good social standing. However, his works were retained in Hamburg. They didn't arrive in Hull until summer 1937. The scheduled exhibition had to be called off. My husband was in the absurd situation of being an artist with no art works. He was terribly depressed. He now had to make a living for both himself and his family as an artist without any tools in a country whose language he did not understand.

My husband was used to settling all his business affairs on his own; I cannot find anything among the papers in his estate relating to this question (looking after his works in Hamburg). I don't even know the name of the shipping company. (In 1945, when he was finally forced to abandon his last studio and - completely embittered, ill and filled with despair - destroyed many of his works, he may have also destroyed a great number of documents and letters from that unfortunate period.)

On 6 November 1936, we were officially married at Saint Pancras Registrar's Office.

(Second child)

...He had brought with him only a few examples of his work, pieces he valued very highly. They were very fine works which he had poured himself, mixing and crafting the materials himself with great love and care, and considerable effort. They consisted mostly of terracotta sculptures and artificial stone works. Originally, they had not been intended for sale, but were due to be shown in the planned exhibition of his complete works. When we ran into hard times, he initially sold one item to the director of the Tate Gallery. And then he sold other works, too. When he received his first order to do a portrait bust he first had to procure some tools. It was impossible to work as an artist in our dreadful attic. Consequently, he had to work at the client's house. He was used to the peace and quiet as well as the concentrated atmosphere that his own studio offered, and suffered unspeakably under these conditions. Having very little money, he was forced to charge very low prices. He bought himself a few wood-carving tools and started to carve wooden bowls in our flat, planning to sell them to some arts-and-crafts shops.

His greatest desire, to work as a sculptor, seemed totally beyond reach. He was very unhappy. When I look back, it was the loss of time, more than anything else, which tormented him most. He often felt unbearably restless and depressed.

Plans for an exhibition are shattered

...My husband set up a small studio in a water-mill, where he worked on a few stones (1936).

In the summer of 1937, our things arrived in Hull from Germany. It was around this time that my husband was asked to model the bust of the well-known English Member of Parliament Mr. George Lansbury. We returned to London (from Willington near Cheltenham - where we had been from May 1936 on). In January 1938, my husband found a studio in Lambolle Road, Hampstead, and a small flat in Parkhill Road. When his works were finally unpacked, it turned out that a lot of the things were no longer in any state to be exhibited. The bronzes had suffered quite a bit and had to be remodelled, while some of the important pieces had been damaged. It was obvious that it would take a lot of work and money to put the damage right again. Around this time, my husband began to cast the works of other sculptors in London, because we were always short of money. The fee for the Lansbury's bust was 150 guineas. He received most of the money in advance payments. This made it possible for us to move from Wiltington, to transport our things from Hull to London, and to pay the first quarterly rent on the studio.

The Leicester Galleries, among others, received individual works from time to time that they wished to show at their various exhibitions. At Lord Yerny's request, a few sculptures were shown in the exhibition "Contemporary art in Osterley Park" in the summer of 1938. Critics working for papers such as the Manchester Guardian, the New Statesman and the Nation showed considerable interest in his works. However, he had missed the best time for staging a comprehensive exhibition. He had lost nearly five precious years, in which he was unable to create any artworks - apart from a few portrait busts, which he found rather unimportant. When he rented the studio in Lambolle Road in 1938, he acquired a few large pieces of Portland stone, which he started to prepare for a large work. However, a shortage of money forced him to continue casting for other sculptors, which absorbed all his time and energy. Even then, we were still permanently in debt and often suffered privations. Our flat in Parkhill Road was, unfortunately, an unhealthy place to live in, desperately in need of repairs, and full of vermin. We had no choice but to move out as soon as possible and rented a small attic flat in Strathray Gardens, NW 3.

In summer 1938, my husband started to model the bust for Lord Lansbury. It was supposed to be cast at Susse Frères in Paris. In February 1939, my husband travelled to Paris at the clients' request (they covered his expenses) so that he could direct the bronze casting. While he was there, he came into contact with Charles Despiau and other well-known Parisian artists. The Salon de Tuileries asked him to do some works for them. He hoped that he would be able to maintain and deepen these relationships.

In May 1939, we moved out of the flat in Strathray Gardens. I moved to Newick in Sussex with the children. My husband had to sleep in his studio in London and could travel to Newick only occasionally.

The trip to Paris and the recognition his work received revived his spirits and gave him fresh hope again. In June 1939, the Landsbury bust was displayed in public and was very well received.

Our plight worsens: Dealing in antiques, work, illnesses

(The outbreak of war) ...Gradually, the orders from foundries in London dried up. My husband started trading with antiques which he tried to obtain from second-hand shops, at auctions and from markets. It was an incredibly arduous task. Our tiny house gradually filled up with broken wares which he put great effort into repairing. (Strawberry Gardens, Newick - day labourer's house) (In 1941 Claude was born, after Jerome and Hussein).

My husband registered unemployed at the labour exchange. He was employed on a drainage project. The work consisted of digging drainage ditches and uprooting trees. That was in the autumn of 1946.

(Hernia))

Later, he worked with a group of immigrant Italian workers on the same project.

(Illness - bronchitis)

In 1944, he was employed as an unskilled worker by the James Chandler construction company in Lewes, which carried out emergency repairs in the heavily bombed districts of South East London. This was when the V2s were being fired across. It was extremely dangerous work, because it mainly involved repairing roofs. He couldn't work in his studio, which was located in North West London, as it was too far away. He rented a small furnished room in Byne Road (SE 26), Sydenham. Whenever possible, he went to Hampstead and tried to work on plans and designs in his studio. In 1945, he was given notice to quit the studio, because the entire property was being put up for sale. It was a terrible blow for him. We had sacrificed everything during those difficult war years so that we could keep the studio. He had hardly any space to store his things, no money and very little energy to organise the move. He destroyed most of his works and sold his tools and turntable to art students in London. Some of his works and drawings were packed and sent to Newick, where we had to stack the boxes in our tiny kitchen. A few things were sent to Byne Road in Sydenham. He kept the room in Byne Road and, from then on, was involved only in antique dealing.

In summer 1947, my husband sustained a slight injury to the middle finger of his left hand. At first, it seemed to be of little consequence, but his health and powers of resistance in general were so weak that the injury simply refused to heal. His finger became inflamed and he had to remain at the Sussex County Hospital, Brighton, for treatment in September 1947. He spent six weeks there. In the end, his finger had to be amputated. His hand remained weak and caused him considerable pain. Any hope of him working as a sculptor again seemed futile. In winter 1949, he was operated on again: this time by a well-known specialist at St. Mary's Hospital in London. The result was disappointing.

In summer 1951, my husband fell ill. He recovered a little and started dealing in antiques again, despite the fact that he was extremely ill. He lived another two years and died as the result of an operation at the Royal Cancer Hospital in Fulham, London, on 29 August 1953.

The above text, written in German by Ruth Abbo in the 1960s, was published in "KUNST IM EXIL in Großbritannien 1933-45", Frölich & Kaufmann, 1986, ISBN 3-88725-218-7.

Translation into English by Robin Benson.